The Transcendental Style of Filmmaking

The transcendental style of filmmaking is the antithesis of the action movie. Action throws everything in your face—lots of cuts, quick editing, and violence. All to negate the mind from introspection. These directors do the opposite. They show you a long take of a static shot. It requires commitment and discipline from the viewer. At first glance, the transcendental style of filmmaking may seem tedious, but it can create a richly fulfilling, spiritual experience. It’s a meditative-like process that allows room for thought and self-reflection.

Filmmaker, Writer, and Critic Paul Schrader wrote a book in 1972 titled, “Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer.” Schrader describes this particular experience in the most concise way I’ve found. In this paragraph, he uses Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovky’s techniques as an example:

“The Tarkovsky long shot is more than long. It’s meditative. The psychological effect of slow cinema’s “long take” is unlike any other film technique. Film techniques are about “getting there,” telling a story, explaining an action, evoking an emotion—whereas the long take is about “being there.” Julian Jason Haladyn, in “Boredom and Art," compares the effect of the long take to a train journey, an early symbol of modernity. The train journey places emphasis on expectation rather than presence. The traveler’s mind is focused on the destination, not whether they are here or now. Travelers can’t appreciate being present because their perception of time and space constantly shifts. Motion pictures, like modernity itself, embraced this constant flux. Slow cinema, specifically the long take, sought to reverse the headlong impetus of technology in favor of the present.” - Paul Schrader.

Tarkovsky didn't invent these techniques. Schrader doesn’t even consider Tarkvosky to be a transcendental filmmaker, but he is very close. He uses the same methods and may even get similar results as directors like Ozu, Pasolini, and Rossellini. But the main difference is Tarkovsky wasn’t worried about his audience relating to his film. A blaring contrast to Ozu’s universal messages about love and family: Tarkovsky was more concerned with putting himself through the theoretical door of transcendence than the audience. Someone like Ozu didn’t do that.

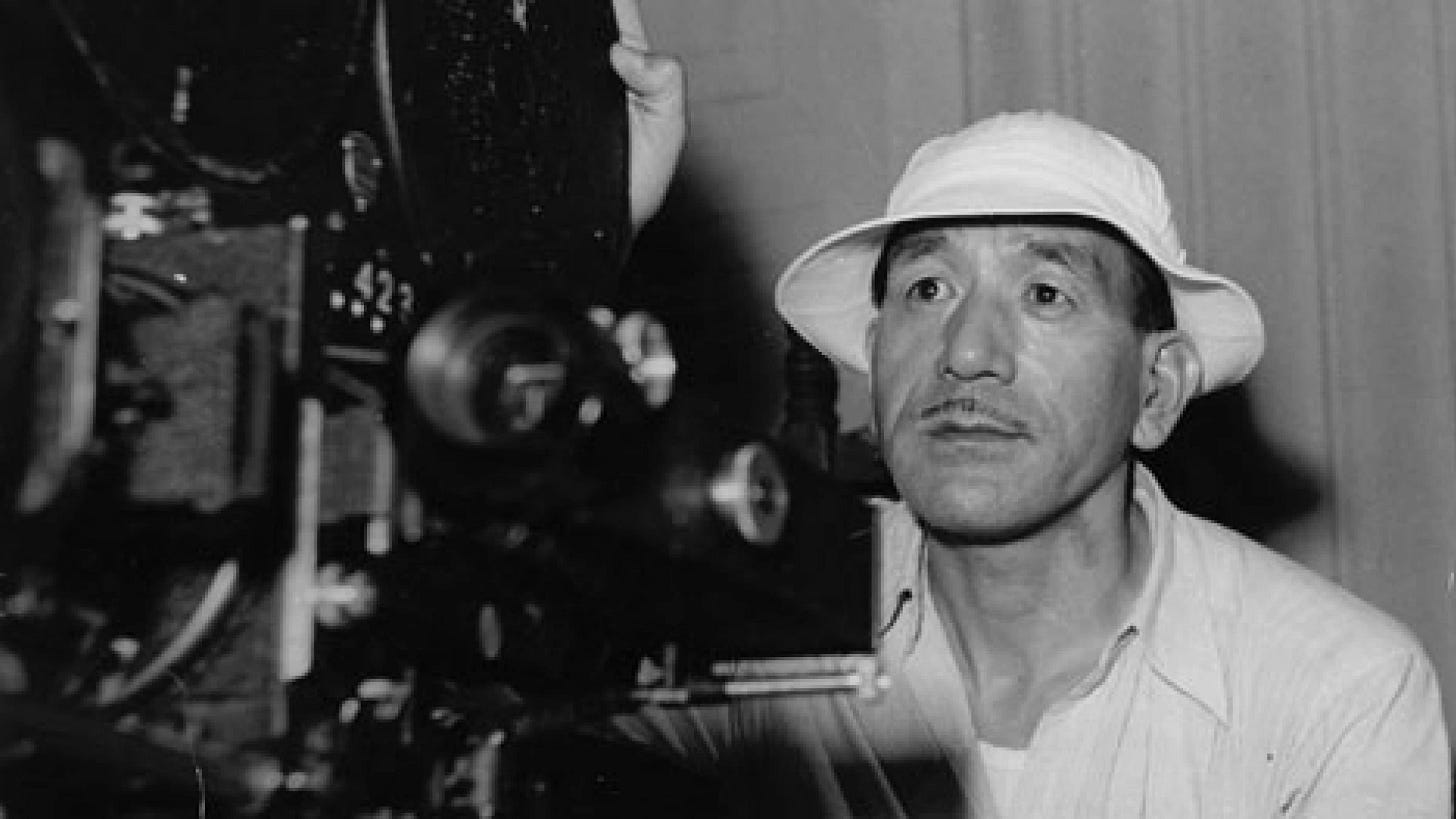

Yasujirō Ozu is a Japanese director focused on familial relations and generational differences. Ozu had an impressive run of films, including “Late Spring” (1949), “Early Summer” (1951), “The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice” (1952), “Tokyo Story” (1953)—which is considered his masterpiece, “Early Spring” (1956), “Tokyo Twilight” (1957), “Equinox Flower” (1958)—his first film in color, “Good Morning” (1959), “Floating Weeds” (1959), “Late Autumn” (1960), “The End of Summer” (1961), and “An Autumn Afternoon” (1962)—his last film before passing away.

As Ozu got older, he slowly eliminated some common-practice filmmaking techniques. Early films like “The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice” show subtle camera movement and more traditional transitions like swipes and fades. Ozu’s last 5-7 films were more refined and focused on transcendence. Ozu’s signature visual aesthetic is a 50mm lens. The camera's height is consistently low to the ground—to emulate the viewpoint of sitting on a tatami mat. It is always static, perfectly framed, and shooting at a closed-down aperture.

I deeply admire Ozu’s restraint in storytelling. As you watch Noriko in “Early Summer,” chat over dinner or have tea with a friend; you get used to her world. You sit in Noriko’s life as her family members pester her to settle down and find a husband. There is a slow, serene ascension of the narrative. When Noriko’s pent-up emotions finally emerge, it’s an almost spiritual feeling for the viewer. You experience the same release of emotions that Noriko does.

The main thing a viewer will notice on the first viewing of an Ozu film is the slow pace. Transcendental films use boredom as a withholding device. Once the viewer gets used to the rhythm and patterns of the film, the audience must be freed from the shackles of their boredom. This is known as the decisive action.

Throughout, An Autumn Afternoon, Hirayama had been a paragon of stoicism; no disaster could perturb his hard exterior. His deeply engrained ironic attitude would let nothing affect him outwardly. So when “nothing” and there is no immediate cause for his weeping—does so radically affect him, it is a decisive action. It is the final disparity in an environment which had become more and more disparate. It demands commitment. If a viewer accepts that scene— if he finds it credible and meaningful he accepts a good deal more. He accepts a philosophical construct that permits total disparity—deep, illogical suprahuman feeling with a cold, unfeeling environment. In effect, he accepts a build such as this: there exists a deep ground of compassion and awareness which man and nature can touch intermittently. This, of course, is the Transcendent. - Paul Schrader

A warm and serene energy washes over you when watching Ozu. Despite the often heartbreaking stories, you can’t help but feel a therapeutic relief. OOzu'sdecisive action is more subtle than other transcendental filmmakers. He evokes empathy in the viewer unlike any other. It's not just empathy for families in the stories but for humanity. He teaches a universal message. No matter who you are, there is an Ozu film for you.

It is almost impossible to describe this experience with text. It requires more than words; transcendental films have so few words. The sounds become more notable. Subtle movements become jumpscares. Everything is calculated.

One of the most famous transcendental films is Chantal Akerman's “Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”(1975), where you watch Jeanne, a lonely widow, do everyday chores. I understand any initial hesitation upon hearing the synopsis of the film. But as previously aforementioned, it requires more than words.

Every detail of this 202-minute hypnotizing experience is planned. Every movement and action is intentional. The last 60 minutes of Jeanne Dielman is so enthralling because of the withholding device that is watching her do chores. I will not spoil the film, but it may be the best use of the decisive action in the transcendental film; you will have to see for yourself.

Another spectacular use of the decisive action comes from the man himself, Paul Schrader. He is famous for writing Martin SScorsese's “Raging Bull” and “Taxi Driver.”He did many influential films, but I want to discuss “First Reformed.”

First Reformed shook me to my core. Schrader takes influence from Bresson's “Diary of a Country Priest.” You got a haunting opening rail shot of the First Reformed church. The rest of the film is in Ozu-like static scenes. You watch Ethan Hawke give a harrowing performance as Pastor Ernst Toller, who has an existential crisis after consulting a climate activist who feels an unbearable dread over bringing a child into a world that will be so catastrophic. Schrader uses the transcendental style of filmmaking he wrote about in 1972 to create one of the most haunting films ever made. It perfectly encapsulates the dreadful feeling around climate change and one losing faith.

I have never found a more impactful art form than the transcendental style of filmmaking. I have loved this genre for months and felt compelled to share. There are many ways to start, but the best way is to go in with an open mind and discipline. It creates a mesmerizing spiritual experience I haven't found in other parts of my life.

Thanks for reading.